PUBG Update Out Now On PC; Full Patch Notes For Season 6 Revealed

PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds Season 6 is officially underway. The new 6.1 update is now available to download for PC players on the live servers, while PS4 and Xbox One owners will have to wait until January 30 to check out the new additions. Below you'll find a rundown on what's new in the Season 6 update, as well as the full patch notes.

Among PUBG's many new additions is a brand-new map, Karakin. It's one of the game's smaller maps, said to introduce a "faster pace and higher tension" to the PUBG experience. The map, located off the Northern African coast, features wide-open and claustrophobic environments both above and below ground. PUBG calls Karakin an amalgam of Miramar and Sanhok, and it holds a maximum of 64 players at a time.

Karakin also comes with a new environmental effect: The Black Zone. Exclusive to the rocky and sandy locale, Black Zones are randomly-targeted spots on the map that get destroyed by massive explosives. This cataclysmic event can utterly level the battlefield or leave areas totally untouched, but the end result is a complete change in map layout. And it all happens in real-time as the match progresses. If you happen to see a purple circle on the minimap, it's best you move locations. Check out Karakin in the screens below.

Elsewhere in the patch, PUBG's sixth season brings two new usable items: a sticky bomb throwable (exclusive to Karakin) and the motor glider vehicle (available on Erangel and Miramar). The sticky bomb adds tactics similar to Tom Clancy's Rainbow Six Siege, wherein certain walls and floors can be used as entry points with the sticky bomb's explosive power. And the moto glider introduces an aerial element, letting you and a friend drop bullets and bombs from the safety of the skies.

The PUBG Season 6 patch notes are quite lengthy and come packed with a variety of changes and fixes. You can read all about the update below, which includes gameplay and sound improvements, matchmaking adjustments, details on the new Survivor Pass, and much more.

Black Zone (Karakin Only)

You need a javascript enabled browser to watch videos.

Click To Unmute

Size:

Want us to remember this setting for all your devices?

Sign up or Sign in now!

Please use a html5 video capable browser to watch videos.

This video has an invalid file format.

Sorry, but you can't access this content!

Please enter your date of birth to view this video

By clicking 'enter', you agree to GameSpot'sTerms of Use and Privacy Policy

enter

Now Playing: PUBG Announces Crossplay | Gamescom 2019

GameSpot may get a commission from retail offers.

Commentary: ‘American Dirt’ is what happens when Latinos are shut out of the book industry

By now, you’ve probably heard about the uproar that took place this week over a book.

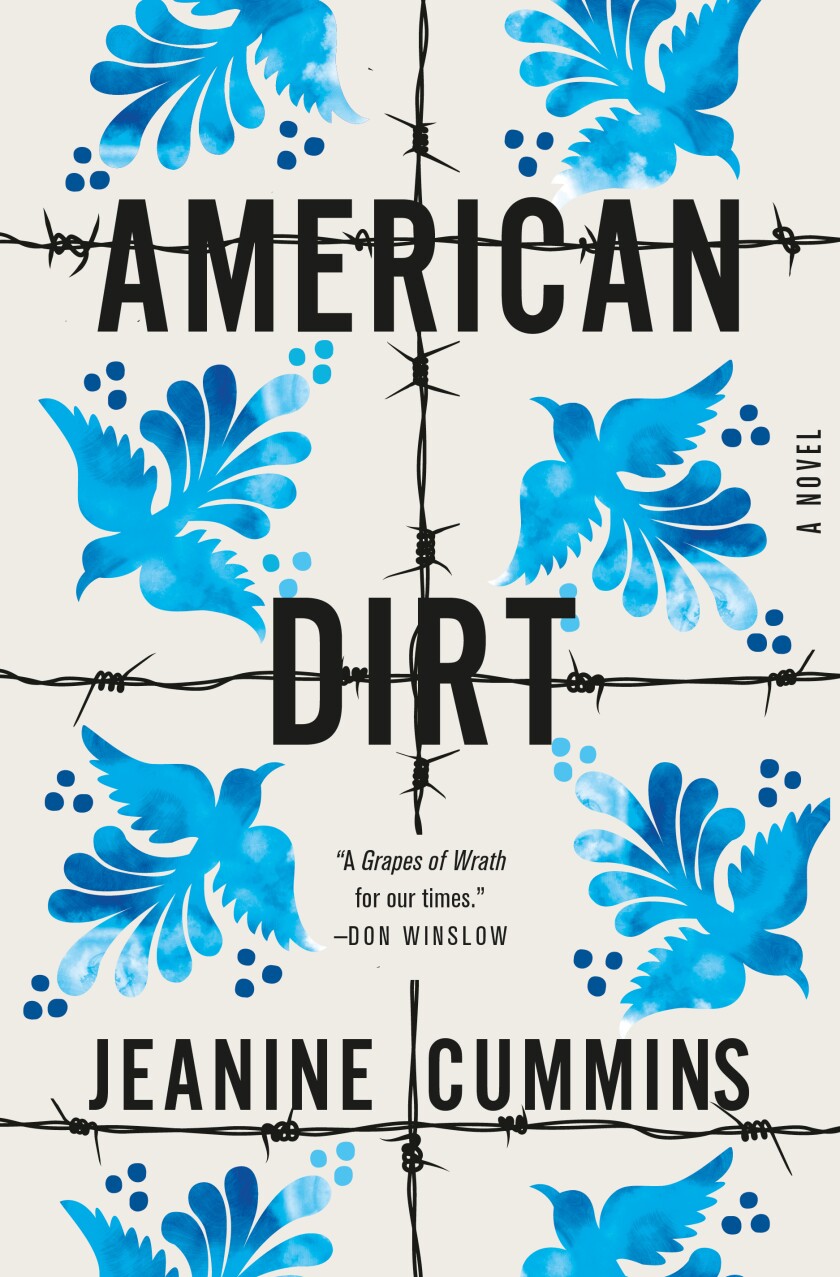

“American Dirt” by Jeanine Cummins was celebrated by critics as the great immigrant novel of our day.

“Masterful.”

“Pulse-pounding.”

“Soul-obliterating.”

“A ‘Grapes of Wrath’ for our times.”

Even Oprah Winfrey dove in early Tuesday morning, the day of the release, and anointed “American Dirt” with the holy grail of endorsements, selecting it for her book club.

“I was opened, I was shook up, it woke me up,” Winfrey said in a promotional video. “I feel like everyone who reads this book is actually going to be immersed in the experience of what it means to be a migrant on the run for freedom.”

It was a perfectly orchestrated mega-budget campaign that might have gone off without a hitch if weren’t for Latinos. Many who grew up in actual immigrant families unleashed a storm of criticism — unlike anything the book industry has seen in years.

I was among those who spoke up.

I’m an immigrant, after all. My family fled by foot and bus to the U.S. in the 1980s as right-wing death squads were killing and torturing thousands across El Salvador, including several of my relatives.

The trauma of those dark days shaped everything about me.

I figured I might recognize some part of my story in Cummins’ book, which follows an immigrant mother and son on their harrowing escape north from Mexico.

Then I read the book. My skin crawled after the first few chapters.

Not because of the suspense, though that’s probably the only thing this narrative does well, like a cheap-thrill narconovela.

What made me cringe was immediately realizing that this book was not written for people like me, for immigrants. It was written for everyone else — to enchant them, take them on a wild border-crossing ride, make them feel all fuzzy inside about the immigrant plight.

All, unfortunately, with the worst stereotypes, fixations and inaccuracies about Latinos.

Sure, I know it’s all fiction and I’m no literary critic. Cummins is not obligated to write a book that reflects my life. But it’s strange that a novel so many are praising for its humanity seems so far from all the real-life immigrant experiences I’ve covered.

Never in nearly two decades of writing about immigrants have I come across someone who resembles Cummins’ heroine, a Mexican woman named Lydia.

She’s a middle-class, bookstore-owning “Mami” who starts her treacherous journey with a small fortune: a stack of cash, thousands of dollars in inheritance money; also an ATM card to access thousands more from her mother’s life savings.

Why is she fleeing? Because while her husband, a journalist, was investigating a drug lord, Lydia was flirting with that same narco.

Moments after he walked into her bookshop, “She smiled at him, feeling slightly crazy. She ignored this feeling and plowed recklessly ahead.”

Later, when Lydia is running for her life, debating whether she and her 8-year-old son should jump on La Bestia, the perilous northbound freight train that’s cost many immigrants their limbs and lives, she has an identity crisis. She used to be “sensible,” “a devoted mother-and-wife.” Now she calls herself “deranged Lydia.”

Because hint, hint, reader: Any immigrant parent desperate enough to put their kids in such danger must be crazy, right?

It’s a book of villains and victims, the two most tired tropes about immigrants in the media, in which Cummins has an “excited fascination” with brown skin, as New York Times critic Parul Sehgal pointed out in one of the few negative reviews of the book. Her characters are “berry-brown” or “tan as childhood.” There is also a reference to “skinny brown children.”

“American Dirt” by Jeanine Cummins was released Tuesday amid a promotional blitz.

(Flatiron Books)

When two of her leading characters, sisters migrating from Honduras named Rebeca and Soledad, hug, “Rebeca breathes deeply into Soledad’s neck, and her tears wet the soft brown curve of her sister’s skin.”

When’s the last time you hugged your sister and stopped to contemplate the color of her skin?

All novelists offer vivid descriptions of their characters, but Cummins’ preoccupation with skin color is especially disturbing in a society that constantly measures the worth of Latinos by where they fall on the scale of brownness.

Soledad, by the way, is also “dangerously” beautiful. She’s a “vivid throb of color,” an “accident of biology.” Even in the “most minor animation of the girl’s body … danger rattles off her relentlessly.”

Of course. Everywhere we Latinas go, our bodies are radioactive with peligro.

Speaking of Spanish, you’ll pick up quite a few words in “American Dirt.” Cummins, in stiff sentences that sound like Dora the Explorer teaching a toddler, will introduce you to conchas, refrescos, “Ándale,” “Ay, Dios mío,” “¡Me gusta!”

All this, it pains me to say, was praised by nearly every U.S. critic who reviewed it as a great accomplishment.

It’s what the Washington Post’s critic “devoured” in a “dry-eyed adrenaline rush,” what kept the Los Angeles Times reviewer up until 3 a.m., what the New York Times initially said had all the “ferocity and political reach of the best of Theodore Dreiser‘s novels.” (The latter paper later deleted the tweet, and an editor explained the line had been from an unpublished draft.)

The heart of the problem is the industry — the critics, agents, publicists, book dealers who were responsible for this project. They’ve shown just how little they know about the immigrant experience beyond the headlines.

So we are left with this flawed book as our model, these damaging depictions at a time when there’s already so much demonizing of immigrants.

Cummins said she questioned whether she was the right person to tell this story.

She was born in Spain and raised in Maryland. A few years ago she identified herself in the New York Times as “white,” though in the book she plays up her Latina side, making reference to a grandmother from Puerto Rico. Her publisher publicized the book by promoting Cummins as “the wife of a formerly undocumented immigrant.” She doesn’t mention that her husband is from Ireland.

“I worried that, as a non-immigrant and non-Mexican, I had no business writing a book set almost entirely in Mexico, set entirely among migrants,” she said in her author’s note.

“I wished someone slightly browner than me would write it.”

Still, she saw herself as a “bridge,” so she plunged in.

I don’t take issue with an outsider coming into my community to write about us. But “American Dirt” so completely misrepresents the immigrant experience that it must be called out.

Cummins said her goal was to help immigrants portrayed as a “faceless brown mass.” She said she wanted to give “these people a face.”

Jeanine Cummins reportedly signed a seven-figure deal with Flatiron Books for her book “American Dirt.”

(Joe Kennedy)

How’s that for a captivating book pitch?

The industry ate it up. In a rare three-day bidding war, Flatiron Books reportedly won Cummins’ book for a seven-figure sum.

The number astounded many writers. It fell with a blunt force on Latinos, who are constantly shut out of the book industry.

The overall industry is 80% white. Executives: 78% white. Publicists and marketing: 74% white. Agents: 80% white.

These numbers include 153 book publishers and agencies, including what’s known in the book world as the Big Five, which control nearly the entire market.

This diversity study, the most comprehensive in the industry, was launched by a small independent children’s book publisher in New York called Lee & Low Books. They’ve conducted it twice, in 2015 and in 2019. (Figures noted above are from the latest study, which will be released Jan. 28.)

In those four years, the numbers showed no significant change.

“The power balance has been off for so long,” said Hannah Ehrlich, director of marketing and publicity for Lee & Low. “Even when a big mistake is brought to their attention, when there’s a sense of urgency, publishers don’t fix it — or they try, with good intentions, but they don’t know how.”

They don’t know how. (Insert emoji of head exploding.)

The solution is simple: Hire more Latinos. More people of color. Listen to them. Promote them. Treat them fairly so they don’t leave.

Ehrlich kindly walked me through the world of publishing, which of course is very similar to journalism, including in its glaring lack of racial diversity.

Often, Ehrlich said, what happens is gatekeepers go looking for good stories, stories that resonate with their view of the world. If they come across a compelling pitch about a person of color, the question becomes, “How do you sell this idea to a broader, mainstream audience?” Translation: white people.

By focusing on one audience, the industry makes it harder for writers of color to break through and also for publishers to build a more diverse customer base.

So it goes, in a long process that many writers of color know all too well, where the best of our stories are frequently sanitized, devalued, tropicalized, manipulated, shrunk down, hijacked.

All for sums that don’t come close to seven figures.

And for deals that don’t get the kind of superstar treatment of “American Dirt.” That includes books that Cummins studied closely to prepare for her novel, with real migrant stories like Oscar Martinez’s “The Beast,” Sonia Nazario’s “Enrique’s Journey,” Luis Alberto Urrea’s “The Devil’s Highway.”

Cummins has no regrets about reaping the benefits of the system. She already got a movie deal and will soon travel to the border with Oprah for more publicity.

“I was never going to turn down money that someone offered me for something that took me seven years to write,” she said in a recent interview.

When asked about the criticism, the author often keeps the focus on the question of appropriation, saying writers shouldn’t be silenced. I have no desire to silence her, but her book is a symptom of a larger problem.

Cummins said people should direct their attention to the publishing world, not individual writers like her.

She’s got a point. In the end, the real fight over “American Dirt” is not about this writer. It’s about an industry that favors her stories over ones written by actual immigrants and Latinos.

Still, it’s hard to let Cummins off the hook. Not when she has posted photos on her Twitter account showing her celebrating “American Dirt” with floral centerpieces laced with barbed wire.

“That’s what I call attention to detail right?!” she wrote in a comment below the photo she posted of the party.

I can’t explain the gut punch I felt when I saw this image on the internet.

Growing up, my family spoke of this barbed wire. How it encircled them, how it tore their hands and legs in their treacherous trek north.

For us, the boogeyman that forced us to leave El Salvador was not some drug kingpin with a quivering mustache like La Lechuza.

It was a brutal 12-year war of terror waged on poor people by oligarchs, backed by the United States, which spent billions to train and equip Salvadoran death squads and the Salvadoran military; the U.S. helped pay for their weapons, bombs, jeeps, uniforms, gas masks. More than 75,000 Salvadorans died in the fighting.

Before my third birthday, I lost just about everyone: My grandfather, uncle and aunt were killed. My father was exiled. My mom was forced to leave me behind in El Salvador to come north.

It’s a story that repeats itself among the hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans who fled to the U.S. in the 1980s.

Because of greed, a thirst for power and government violence in Central America — a place where the United States has heavily intruded since the 1800s — thousands of families continue to run north. From Honduras. From Guatemala. From El Salvador.

This is the immigration story of our times.

Hopefully, soon, the book world will gather the nerve to let more of our own writers tell it. And give that story the same royal treatment it gave “American Dirt.”

Readers critique The Post: What are these popular children’s books really about?

Although we read to our children and then encourage them to read independently, I suspect we adults are finding less and less time to read to ourselves. There’s work, and then more work, and, when we’re finally done, there’s the endless glow from our smartphones, devices that are portals to a bottomless web of information and disinformation from which we emerge both richer and poorer but decidedly less well-read.

Yosef Lindell, Silver Spring

In his article on the New York Public Library’s list of the 10 most checked-out books in its 125-year history, Ron Charles implied that the popularity of “1984” was “distressing” because the dystopian world it depicts “has not been enough to keep it from coming true in America.” This suggests Charles does not understand what “1984” is really all about.

While it’s commonly believed that George Orwell’s vision of the future was a “totalitarian society under constant surveillance and devoted to a cult of personality that suffers no dissension,” it might be helpful to remember that nowhere in the novel does Orwell offer even a hint of the political bent of the regime. Whereas we are conditioned to equate totalitarianism with the right wing, Orwell knew better. Thus it would be even more helpful to know what Orwell himself was trying to convey, i.e., that a people divested of their history can be made to believe anything because they have no point of reference. To wit: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.” And, “There are some ideas so wrong that only a very intelligent person could believe in them.” And, “So much of left-wing thought is a kind of playing with fire by people who don’t even know that fire is hot.” Orwell popularized the terms “thoughtcrime” and “Thought Police.”

This brings us to another of the books, Ray Bradbury’s masterpiece, “Fahrenheit 451.” Again, Bradbury never tells us the political bent of the forces the fireman, Guy Montag, serves. We know only that they want to censor literature and destroy knowledge, and it’s Montag’s job to burn books. In the end, Montag becomes disillusioned, quits his job and commits himself to preserving the written heritage of the past. In fact, “Fahrenheit 451” is a story with a conservative perspective.

So I’d ask here, who today wants to censor and control language, thought and culture? The comparison between “Fahrenheit 451” and the film “The Lives of Others,” which won the Academy Award for best foreign language film of 2006, is eerie especially because “Lives,” while fiction, is a story that occurs in a real place: East Germany in the late 1980s.

Lawrence Cherney, Annandale

More muddying than myth-busting

In his Jan. 12 Outlook essay, “Five myths: War powers,” Scott R. Anderson created rather than dispelled at least two fundamental war powers myths.

Contrary to Anderson’s assertion that Congress is effectively handcuffed in employing the power of the purse to stop war, Congress did so in 1973 to end U.S. hostilities in Indochina. Section 307 of Public Law 93-50 provided: “None of the funds herein appropriated under this act may be expended to support directly or indirectly combat activities in or over Cambodia, Laos, North Vietnam, and South Vietnam by United States forces, and after August 15, 1973, no other funds heretofore appropriated under any other act may be expended for such purpose.” Since then, Congress has cowardly bowed to limitless executive war power to avoid hard political votes.

Also contrary to Anderson, Congress alone is empowered under the Constitution’s declare war clause to commence war, leaving the president power to respond to sudden or imminent aggression against the United States. Alexander Hamilton, ardent champion of a muscular executive, spoke for every participant in the drafting and ratification of the Constitution in confirming: “ ‘The Congress shall have the power to declare war’; the plain meaning of which is, that it is the peculiar and exclusive province of Congress, when the nation is at peace, to change that state into a state of war; whether from calculations of policy, or from provocations or injuries received.”

George Washington and many others of the founding generation echoed that understanding. Yet the executive branch, including Attorney General William P. Barr, takes the Orwellian view that the three-year presidential Korean War involving millions of U.S., Chinese and Korean soldiers and risking use of nuclear weapons did not require a congressional declaration or equivalent authorization.

The writer was associate deputy attorney general under President Ronald Reagan from 1981 to 1983 and author of “American Empire Before the Fall.”

Misplacing blame

In her Jan. 14 Metro column, “Va. could right a 100-year-old wrong,” Petula Dvorak wrote, “Virginia has a 100-year-old debt to pay.” She claimed this is a debt Virginia owes for “arresting, imprisoning and abusing” women’s suffrage advocates at the Women’s Workhouse in Occoquan over a century ago. Supposedly, Virginia can atone for this now by passing the Equal Rights Amendment.

Though there may be valid reasons for Virginia to pass the ERA, the disturbing events described by Dvorak are not among them. As she must know — and as a simple Internet search confirms — the Women’s Workhouse in Occoquan was a District of Columbia institution, established by an act of Congress and built on condemned land in Virginia. It thus had nothing to do with Virginia other than the accident of its location. It could just as easily have been located in Maryland, as other District institutions were.

For The Post to publish uncritically such misinformation is not only ahistorical but also dangerous. In an area where so many residents are from somewhere else and lack knowledge of local history, it may lead to important actions based on a misunderstanding of events.

David W. Stanley, Washington

The terrible obstacle Jewish refugees faced

“When U.S. universities turned refugees away,” Michael S. Roth’s Jan. 12 Book World review of “Well Worth Saving: American Universities’ Life-and-Death Decisions on Refugees From Nazi Europe,” by Laurel Leff, stated that “hundreds of thousands” of refugees fleeing Nazi Germany and hoping to immigrate to the United States had to compete for “the small quota of visas available.” Actually, the immediate obstacle to their immigration was not the number of visas but the harsh way in which the Roosevelt administration administered them.

The administration suppressed Jewish refugee immigration far below what the law permitted. The annual quotas for immigrants from Germany and, later, Axis-occupied countries were filled in only one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 12 years in office; in eight of those years, those quotas were less than 25 percent full. Some 190,000 quota places that could have saved lives were never used, because the Roosevelt administration piled on extra requirements and bureaucratic obstacles to discourage and disqualify Jewish refugees seeking to come to the United States.

Rafael Medoff, Washington

The writer is director of the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies.

Carson = Castro

The Jan. 10 editorial “A retreat on fair housing” mentioned Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson more than either President Trump or former president Barack Obama. If this is a Carson action, then why wasn’t the 2015 rule a former HUD secretary Julián Castro action rather than Obama’s?

Specifics, please

However, the article also declared that Americans in rural areas “watch the same cable TV talk shows and read the same national news websites as people anywhere else” without providing any supporting data. Left unsaid was the percentage of conservative-to-right-wing news sources (Fox News, National Review, Breitbart, InfoWars, etc.) compared with moderate-to-liberal-skewing news sources (NPR, Politico, the New York Times, the Guardian, etc.) that these rural populations consume.

Given the degree to which specific news sources shape political opinions as well as determining a grasp of reality, a more in-depth comparative analysis of the rural vs. urban news sources would have given readers a better perspective on why the divide between these two populations continues.

A gentleman and a scholar

The obituary also ignored Scruton’s ties to the Washington area. Between 2004 and 2009, his primary residence was in Sperryville, Va. He had affiliations with two Washington think tanks: the American Enterprise Institute, where he was a visiting scholar, and the Ethics and Public Policy Center, where he remained a senior fellow until his death.

Martin Morse Wooster, Takoma Park

A fuller background

While I have no particular opinion regarding the merits of his argument, I do, as a general practice, like to know a person’s credentials and background before deciding how much weight to give his opinion. The blurb at the end of the op-ed said Ellis was a former columnist for the Boston Globe and editor of News Items, a political newsletter. A little digging at Wikipedia revealed that he is a cousin to former president George W. Bush and former Florida governor Jeb Bush and works with a venture capital firm. Even more telling, he was a consultant for Fox News during the 2000 election. While this information does not necessarily negate his argument, it cast light on how readers should evaluate his opinion and arguments. The Post should provide readers with more information regarding op-ed contributors so we can make informed decisions. In this instance, it failed.

Bill Reynolds, Tallahassee, Fla.

How do black boys get coverage?

I seldom read the Sports section, but I flick through it occasionally. I was stopped on Jan. 16 by Kevin B. Blackistone’s thoughtful column, “Suicide rate of black teens rises into crisis territory,” about suicides among black teen boys and a Congressional Black Caucus report on the issue.

Is having a connection to sports the only way black boys will get coverage? This is a national issue, so why was it buried on Page 3 of the Sports section? Would it not contribute to the national awareness and conversation if the newspaper of the nation’s capital discussed this in a newsier section? As a service to our children and their mothers, please consider this a more newsworthy topic.

Sarah Zapolsky, Alexandria

The wrong take on China

Fareed Zakaria’s statement in his Jan. 17 Friday Opinion column, “Why Trump caved on China,” that “Beijing has not gone to war since 1979, a record of nonintervention that makes it unique” was incorrect. Beijing fought a bloody 10-year border war with Vietnam that only started in 1979.

The Chinese Navy attacked Vietnamese naval vessels in the South China Sea in 1988, sinking several Vietnamese ships and killing dozens of Vietnamese sailors.

To this day, Beijing continues to use the threat of military force against other countries in support of its dubious territorial claims in the South China and East China Seas.

Merle Pribbenow, Falls Church

The writer is a retired CIA Vietnam specialist, Vietnamese language translator and author of a number of articles on Vietnamese military history.

The real payoff of a liberal arts education

I have become increasingly frustrated and perhaps bored by debates on the value of a liberal arts education or, indeed, a college education at all.

Education is frequently confused with job training. Yes, a college degree is expensive: Don’t buy it if you can’t afford it. If you buy and finance a car, do you not plan to make those payments and enjoy the car driving places you want to go? If you go to a liberal arts college, do you not plan to make the payments and enjoy the learning you obtained? And to carry that on, if you can’t afford a BMW, get a Chevrolet.

I do not remember my father, hardly a wealthy man but one who sent two daughters to liberal arts colleges, ever suggesting that we were there for vocational training. If so, he certainly would not have let me major in fine arts and English literature. No, he said to get a grounding in many subjects: art and music and history and geology and literature and writing and critical thinking and debate and, if I could pass them, even some mathematics courses. (There was some well-founded doubt.)

And then go to secretarial school or nursing school or cooking school or even become an electrician for your vocational education.

Does a liberal arts education “pay off”? It clearly depends on your values. If job training is the objective, go to trade school. If a love of lifelong learning is the objective, go to a liberal arts college. And besides, it will make you enjoy “Jeopardy!” even more as you shout out answers in many categories.

Start the timeline earlier

The timeline of events in the Jan. 12 news article “How U.S. sanctions are paralyzing the Iranian economy” stated that Iranian strikes against U.S. military bases were “retaliatory” and “triggered” by the U.S. killing of terrorist and Iranian military mastermind Maj. Gen. Qasem Soleimani.

If that is the case, then how does The Post account for the recent downing of a U.S. drone, the killing of a U.S. contractor and the attack on the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, all of which pre-dated the U.S. retaliation? Why start the timeline after the United States or its allies respond to aggression by its enemies?

Michael Berenhaus, Bethesda

Fielding errors

First, the article said the Astros cheating scandal was “the best news since the Washington Nationals won the World Series” but provided no explanation for this statement. Second, the sentence, “It’s time to get the cheaters out of sports” appeared twice in this brief piece.

Sure, that’s an important concept for kids to learn, but so is: All materials for publication deserve top-notch copy editing.

No comments:

Post a Comment